By Zach Klitzman

In the wake of Lincoln’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, waves of support reached the president. A dozen governors from loyal states met the President four days after the Proclamation’s release, and “congratulate[d] the President upon his proclamation, believing it will do good as a measure of justice and sound policy.” In response, Lincoln, according to the Republican New York Tribune, said “no fact had assured him so thoroughly of the justice of the conclusion at which he had arrived as that the Executives of the loyal States gave it their hearty approbation.”[1]

On September 25, Vice President Hannibal Hamlin—one of the staunchest abolitionists in Lincoln’s cabinet—wrote him a letter expressing his “sincere thanks for your Emancipation Proclamation.” Writing from Bangor, Maine, Hamlin had no doubt that the Proclamation was a watershed moment in American history. “It will stand as the great act of the age. It will prove to be wise in statesmanship as it is patriotic. It will be enthusiastically approved and sustained, and future generations will, as I do, say God bless you for this great and noble act.”

However, Lincoln did not have the luxury of looking ahead to future generations. Instead, he had a much more pessimistic, albeit realistic, view of the immediate reaction to the proclamation than either the governors or Hamlin did. In a “strictly private” response to Hamlin on September 28, 1862 (exactly 149 years ago), Lincoln warned his subordinate that “It is known to some that while I hope something from the proclamation, my expectations are not as sanguine as are those of friends. The time for its effect southward has not come; but northward the effect should be instantaneous.” Those northward effects were not just “commendation in newspapers and by distinguished individuals,” but included those of a negative nature. “The stocks have declined, and troops come forward more slowly than ever. This, looked soberly in the face, is not very satisfactory…. The North responds to the proclamation sufficiently with breath; but breath alone kills no rebels.” Lincoln ended his grave letter with an apology of sorts: “I wish I could write more cheerfully; nor do I thank you the less for the kindness of your letter.”[2]

Lincoln, though grateful for the praise of his Proclamation, realized that the North was not yet willing to back up their vocal support with action. He received even more evidence in the November Congressional elections. Republicans lost 22 seats in the House of Representatives, while the Democrats picked up 28. That net of 50 seats totaled 27 percent of the 185-member House. Though the issue of emancipation helped gain votes in New England, it had a negative impact in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and New York.

Despite the electoral backlash to emancipation—and to be fair, the war’s slow progress also hurt the Republicans—Lincoln refused to back down on his promise of emancipation. As reported in the New York Tribune, he declared to a group of Union Kentuckians in late November “that he would rather die than take back a word of the Proclamation of Freedom.”[3]

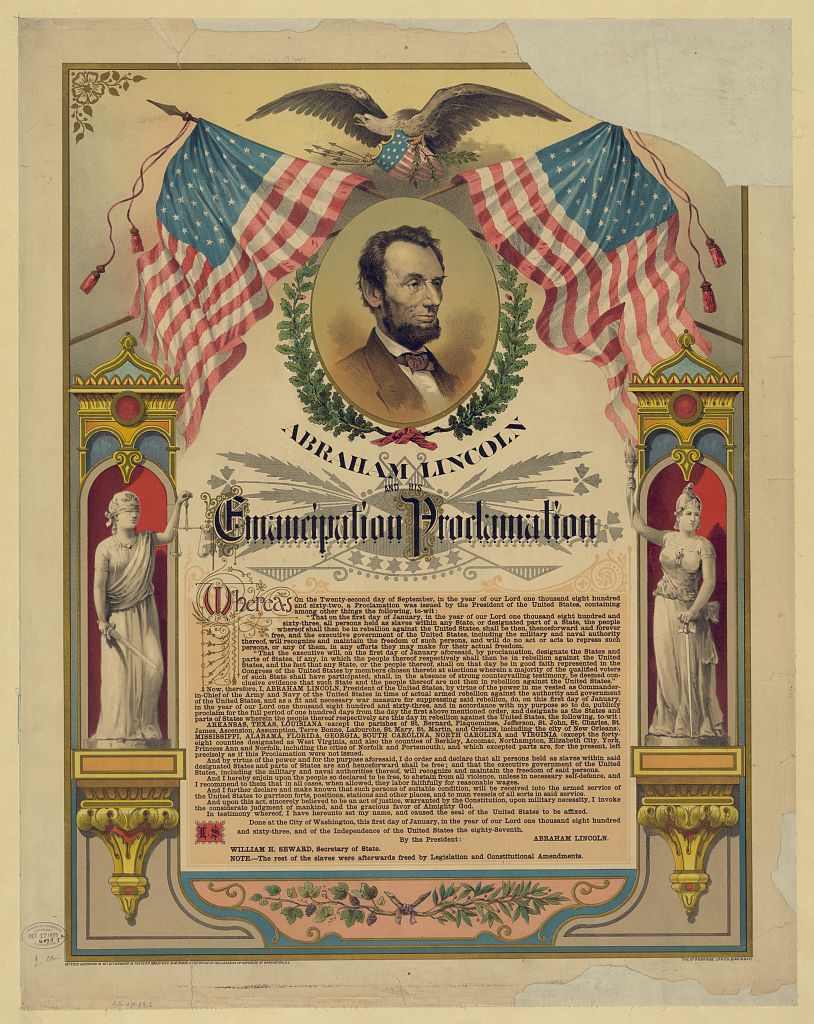

Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Mr. Klitzman is the Executive Assistant at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

[1] “Reply to Delegation of Loyal Governors,” September 26, 1862, Roy P. Balser, ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 5: 441.

[2] “To Hannibal Hamlin,” September 28, 1862, Collected Works 5: 444.

[3] “Remarks to Union Kentuckians,” November 21, 1862, Collected Works 5: 503.