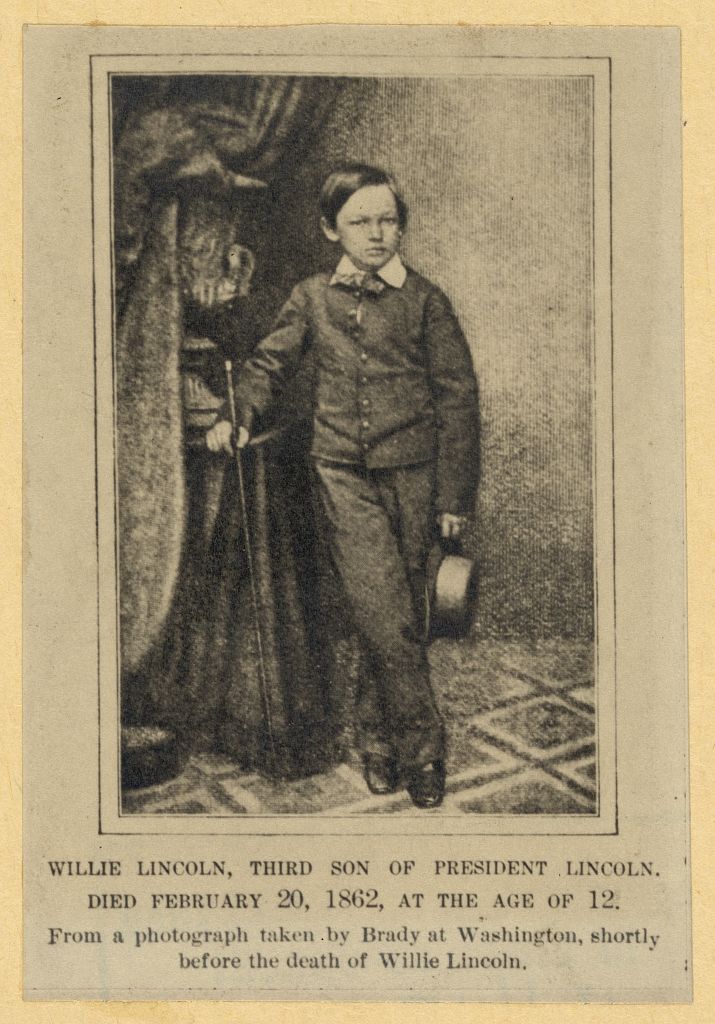

On Thursday, February 20, 1862, Abraham and Mary Lincoln were reeling from the death of their second-oldest surviving son, Willie. He had died from what was likely typhoid fever.

Willie had gotten sick in January. The Lincolns had gone ahead with a February 5th reception they’d planned long before Willie came down with typhoid. They were worried and throughout that evening both Mary and Lincoln left the party to check on him. When he showed improvement, the Lincolns were able to rejoice in Grant’s victory at Fort Donelson in Kentucky on February 16th. However, Willie went downhill rapidly after that and on Thursday, Feb. 20th, at 5:00 p.m., he died.

Their youngest son, Tad, had come down with the disease in February, too, and Mary had been caring for both boys. Once Willie died, Mary was inconsolable. Several cabinet members’ wives cared for Tad until Lincoln was able to hire a nurse, Rebecca Pomroy, who came highly recommended by Dorothea Dix. Mary withdrew from anyone or anything that reminded her of Willie. She got rid of his things. She wouldn’t go into the room in which Willie died. She asked that Willie’s young playmates, Bud and Holly Taft, not come to the funeral; they reminded her of Willie and she couldn’t bear seeing them. As it turned out, she didn’t attend the service itself. She only went to the private gathering in the Green Room before the public service and then returned to her bedroom.

Most illuminations in the city to celebrate Grant’s western victory and George Washington’s birthday were cancelled. People noted Willie’s death in their journals, and the White House was draped in black. Lincoln invited Bud Taft, who had sat with Willie during his illness, to come “see Willie before he was put in the casket” (Team of Rivals, p. 420) without Mary’s knowledge.

On February 24, Phineas Gurley, the pastor at New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, conducted both the private service for the family at noon and the public service in the East Room at 2:00. He conveyed a message of comfort and spoke about the mystery of the providence of God to the attendees, which included Vice-president Hannibal Hamlin, cabinet members, senators and congressmen, diplomats, soldiers and friends. At the conclusion of the service, Lincoln rode with son Robert, Orville Browning and Lyman Trumbull, Illinois friends and senators, to Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown.

Mary remained in bed for three weeks. Lincoln grew more and more concerned about her. She blamed herself for Willie’s death and felt God was punishing her for her vanity. As Tad continued his recovery, Lincoln spent as much time with him as possible; what work he could do in Tad’s room, he did there. And as Tad got stronger, LIncoln and Tad became closer. Tad needed the comfort of his father and the assurance that he was nearby. Lincoln continued his work as president (in particular, he was struggling with General McClellan’s inaction), but he grieved for his lost son. For several Thursdays following Willie’s death, Lincoln went into the Green Room to mourn. He, unlike Mary, wanted physical reminders of Willie … a picture, a scrapbook … near him.

As I look out my window today, I’m reminded by the evidence of nature, as the Lincolns most surely were, that life continues, but I can’t help feel how very difficult those weeks following Willie’s death must have been for them. I’m also awed by Lincoln’s strength of character to continue his duties in spite of on-going and painful trauma.

Ms. Roberts is a Historical Interpreter at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005, pp. 415-423.

Keckley, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes in The Lincoln White House: Memoirs of an African-American Mistress. New York: Dover Publications, 2006, pp. 42-46.

White, Ronald C., Jr. A. Lincoln. New York: Random House, 2009, pp. 474-480.