Editor’s note: this article first appeared in the Fall 2015 newsletter. All images are used courtesy of the Library of Congress.

by Jason Silverman

During the past four years the nation has experienced the celebration of the sesquicentennial of the American Civil War. From major battles to skirmishes, from grand events to major speeches, from constitutional amendments to laws and acts, commemorations took place to remind us of what occurred during the four years of the nation’s defining moment. Yet, lost in all of this media and scholarly attention was one of President Lincoln’s signature pieces of legislation, the Act to Encourage Immigration signed July 4th, 1864 – the first and only major law in American history to encourage immigration. Given that immigration is in the news today on a daily and global basis, this is, sadly, a significant omission of an act that President Lincoln saw as the bright future of the United States.

There seems to have been no significant pressure for governmental encouragement of immigration until President Lincoln, in his Annual Message to Congress on December 8, 1863, called for government assistance. “I again submit to your consideration the expediency of establishing a system for the encouragement of immigration. All though this source of national wealth and strength is again flowing with greater freedom than for several years before the insurrection occurred, there is still a great deficiency of laborers in every field of industry, especially in agriculture, and in our mines, as well as of iron and coal as of the precious metals. While the demand for labor is thus increased here, tens of thousands of persons, destitute of remunerative occupation, are thronging our foreign consulates and offering to emigrate to the United States if essential, but very cheap assistance, can be afforded them. It is very easy to see that under the sharp discipline of Civil War, the nation is beginning a new life. This noble effort demands the aid and out to receive the attention of the Government.”

That part of the President’s message referring to immigration prompted Congress into action. Little more than a week after Lincoln’s message a bill to encourage and protect foreign immigrants and to make more effective the Homestead Act, which had become law on May 20, 1862, was presented in the Senate. Two weeks later Lincoln’s words on immigration were referred to a special committee of five on immigration, chaired by Elihu B. Washburne of Illinois. From there a bill to establish a formal Bureau of Immigration was introduced shortly after the New Year.

Lincoln’s law was then moved forward by Senator John Sherman of Ohio, chairman of the Committee on Agriculture. The committee shared Lincoln’s belief that the encouragement of immigration was of the highest importance and in their report stated that “labor has special wants in every department of industry; vacancies caused by recruiting calls for a large increase in foreign immigration to make up the deficiency at home. Furthermore, the South, after the war is over, will present a wide field for voluntary white labor and it must look to the immigrant for its supply.”

Elihu Washburne

A bill was finally passed on March 2, 1864, containing the recommendations of the Senate Committee. It provided for a Commissioner of Immigration under the State Department, who was to encourage immigration by collecting and circulating in Europe such information about America as would encourage immigration to the United States. The Commissioner was to correspond with various consuls at European posts who were to aid him in his work. An office was to be established under a Superintendent at New York, whose duty it was to protect immigrants from frauds, to make contracts with railroad companies for the transportation tickets to be paid for by the immigrant, and in general facilitate their travel to their destination or the place where their labor would be most productive. He was also to see that the Passenger Act of 1855 was enforced to ensure the well-being of travelers to America. President Lincoln could, under this bill, appoint a Superintendent of Immigration at New Orleans, if in his judgment the public service required it. Fifty thousand dollars were to be appropriated.

In a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives on February 27, 1864, in support of the bill, Representative Ignatius Donnelly emphasized that the need for labor was so great, that private enterprise had sought to remedy it by establishing societies in Boston and elsewhere to encourage and facilitate immigration. “Let us stimulate, facilitate and direct that stream of immigration,” he declared, “throw wide the doors to emigration…and in twenty years the results of the labors of the immigrant and their children will add to the wealth of the country a sum sufficient to pay the entire debt created by this war.”

Donnelly asserted that he hesitated to ask Congress to advance a large sum of money to aid immigration, although he believed that such would seem to be the preference of President Lincoln. By April, Representative Washburne reported from the special committee in the House a bill to encourage immigration. In its report the Committee said: “The vast number of laboring men, estimated at nearly one million and a quarter, who have left their peaceful pursuits and patriotically gone forth in defence of our government and its institutions, has created a vacuum which has become seriously felt in every portion in the country.”

[teaser] READ: The Republican Party’s 1864 platform encouraging “liberal and just policy” on immigration [/teaser]

Donnelly continued: “Never before in our history has there existed so unprecedented a demand for labor as at the present time. This demand exists everywhere. It exists in the agricultural districts of the southwest, in the central states; in New England, and among the shipping interests of the lakes and seaboard, and is felt in every field of mechanical and manufacturing industry. The dearth of laborers is severely felt in the coal and iron mines of Pennsylvania; in the coal mines of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois; in the lead mines of Galena, and in the gold and silver mines of California, Nevada, Idaho, and Colorado. There are twenty railroads now in process of construction or under new contract in the west alone, which would furnish employment for twenty thousand laborers. The construction and repair of railroads in other sectors of the country will give employment to ten thousand more. It is believed that the demand for laborers on our railroads alone will give employment for the entire immigration of laborers in 1864.”

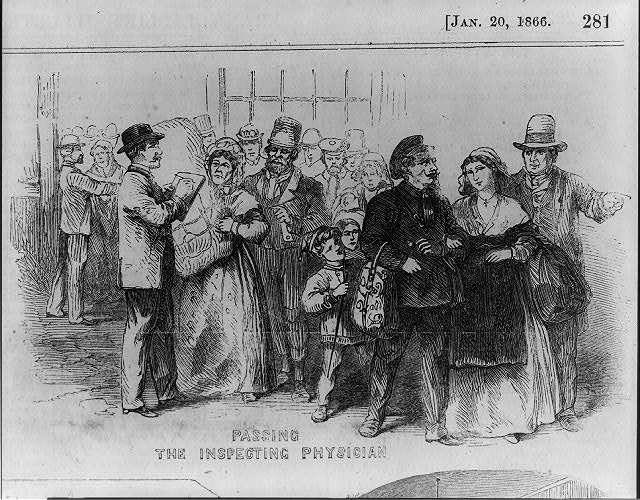

Immigrants arriving in New York City, undergoing health inspection in 1866

The bill presented for consideration did not propose the establishment of any independent bureau, but for the Commissioner of Immigration to be under the direction of the Department of State. It further provided that contracts may be made whereby emigrants should pledge the wages of their labor to repay the expenses of their transportation. The Secretary of the Treasury, under the direction of President Lincoln, was empowered to reduce the tonnage duties on vessels which would bring in immigrants. A United States immigrant office in New York City under the Superintendent of Immigration was established to facilitate the transportation of immigrants, to protect them against fraud, and to make contracts with railroad and transportation companies for tickets for the immigrants.

Symbolically, and appropriately, the bill became a law with Lincoln’s signature on July 4, 1864. The Act in its final form consisted of eight sections, and authorized the President, by and with the consent of the Senate, to appoint a Commissioner of Immigration for a term of four years at $2500 per annum.

[teaser]READ: The text of An Act to Encourage Immigration[/teaser]

The second section provided: “That all contracts that shall be made by emigrants to the United States in foreign countries, in conformity to regulations that may be established by the said commissioner, whereby emigrants shall pledge the wages of their labor for a term not exceeding twelve months, to repay the expenses of their emigration shall be held to be valid in law, and may be enforced in the courts of the United States, or of the several states and territories; and such advances, if so stipulated in the contract. . . . But nothing herein contained shall be deemed to authorize any contract contravening the Constitution of the United States, or creating in any way the relation of slavery or servitude.”

Section three exempted all immigrants arriving after the passage of the act from compulsory military service unless the immigrant voluntarily renounced under oath, his allegiances to the country of his birth and declared his intention of becoming a citizen of the United States.

Section four provided for the establishment of a United States Emigrant Office at the city of New York, under a Superintendent of Immigration with an annual salary of $2000. He was able to make railroad and transportation contracts for tickets to be furnished to the immigrants, facilitate their travel to their destination, and enforce the Passenger Act. These duties were to be carried out under the direction of the Commissioner of Immigration.

The fifth section disqualified any person either directly or indirectly involved in any corporation having land for sale to immigrants. The seventh section provided for an annual report to Congress by the Commissioner on the expenditures made and which included the statistics of foreign immigration. And the concluding section appropriated $25,000, or any part of it, as a discretionary fund to be used by the President as he saw necessary for the recruitment of immigrants.

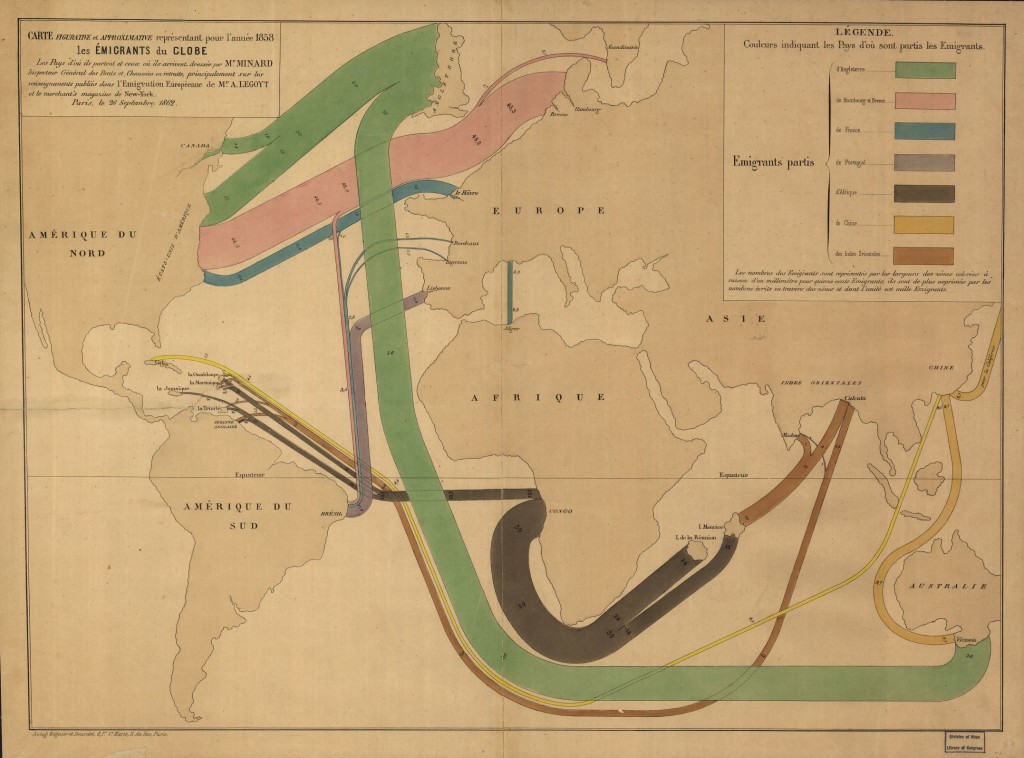

Worldwide immigration flows from 1858

This Act to Encourage Immigration undoubtedly had received backing from employers of labor because their interests dictated such support. President Lincoln’s message on this subject seems to have begun a wave of support for federal action and other plans to encourage immigration which lasted well into the next decade. One contemporary newspaper that supported the immigration of labor was the Hardware Reporter and it enthusiastically welcomed Lincoln’s message “Future historians,” said an editorial, “will assign a most important place in history” to this message. “Surely no more profitable use of the people’s money could be made in expending a moderate sum in facilitating emigration of a large number of laborers, especially skilled workers, to this country. We hope,” the editorial continued, “Congress will promptly do its duty but in the meantime let not the employers of labor remain idle, but rather by combined and systematic effort seek to influence at once an increased volume of emigration from Europe.”

Lincoln’s message seems to have strongly motivated at least one diplomat, W.W. Thomas, Jr., stationed at Gothenburg, Sweden, who wrote to the Assistant Secretary of State, Frederick Seward, that he was encouraging Scandinavian emigration by distributing information in every way within his power. He also recommended “that two or three unaccredited agents, who speak Swedish and are acquainted with this country, be sent with the first vessel to make known the demand for labor in the United States and the inducement of immigration.”

In April 1864, John Williams, editor of the Hardware Reporter, penned an editorial in which, while opposing complete government control over the importation of laborers, strongly maintained that the obligation rests with the government to provide the means by which the great shortage of labor might be rectified. “It is a matter of national interest,” said Williams, “and should be provided for at national expense.”

So strong had the support for the encouragement of immigration become that Lincoln’s Republican Party in its 1864 convention wrote into their platform a principle stating: “That foreign immigration, which in the past has added so much to the wealth, development of resources, and increase of nations, should be fostered and encouraged by a liberal and just policy.”

While the Act to Encourage Immigration of July 4, 1864, did not provide for the establishment of an independent Bureau, the State Department under Secretary William Seward used its own discretion and created the Bureau of Immigration. During its short lifetime of three years, it had four Commissioners of Immigration assigned to Washington (in order they were James Bowen, H.N. Congar, E. Peshine Smith, and R.S. Chilton), and one superintendent in New York City, John P. Cumming, subordinate to the Commissioner.

The Bureau worked steadily to increase both encouraged and voluntary immigration. According to one report, “It approved of contracts between immigrant and employer and looked for private parties to take laborers under contract; it tried to restrict the activities of certain contract labor companies and it cooperated with others; it was entrusted with the enforcement of the passenger law; it made contracts for selling tickets with both railroad and transportation companies; it prevented imposition upon immigrants; it encouraged States to pass laws to encourage immigration and to cooperate with the Bureau; it collected statistics, on both labor and immigration; and it published and widely circulated a pamphlet in English, German and French.” In all of this, it worked through the State Department with its vast diplomatic network.

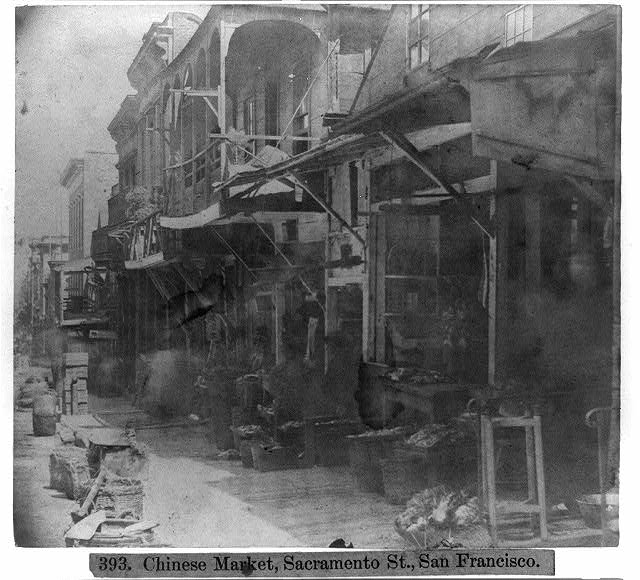

Numerous queries were received especially from the former slave states asking permission to import Chinese laborers. In all of these instances the Bureau rejected the requests and pointed out that it considered the importation of Chinese laborers a violation of the California “Act to Protect Free White Labor Against Competition with Chinese Coolie Labor, And to Discourage the Immigration of the Chinese into the State of California,” or commonly known as the “Anti-Coolie Act of 1862” which had attracted increasing support in the nation’s capital.

While the Federal Bureau did not keep in active contact with the various immigrant importing agencies, it did work very closely with one of these companies, the American Emigrant Company. As soon as the Act to Encourage Immigration was passed, the American Emigrant Company established an office in New York City at No. 3 Bowling Green. “This company,” will be the “handmaid of the new Bureau of Immigration,” said an editorial in the Hardware Reporter, “applying private enterprise just at the point where official interference becomes impracticable.” This statement quickly proved prophetic when the Bureau of Immigration opened in New York City, in of all of the places, to choose, No. 3 Bowling Green, the exact same office space!

One aspect of the work of the Federal Bureau to Encourage Immigration during the Civil War was to direct immigrants to that section of the country where there was a shortage of labor, and where labor could receive the highest wages. To accomplish this, the Bureau sent letters to more than one thousand agricultural societies requesting a statement of wages paid to the mechanics, artisans, and common laborers.

Many of the requests that the government received from immigrant groups abroad for aid to immigrate to the United States were forwarded through the consular system to the Bureau of Immigration. Some of these groups were misinformed and expected the government to pay their expenses to America. One individual, J.D.B. Curtis, whose family owned 300,000 acres of land in Florida, requested the government to help him pay for the transportation of 3000 to 7000 settlers to that state to help him build a model colony, “where God will be glorified. . . . And children made better than their fathers. The colonists will be faithful to the Union and opposed to slavery, and, if I obtain a large number [will] control the political destiny of the State.”

The difficulties the Bureau encountered in enforcing the passenger laws, the dissatisfactions the private companies encountered in respect to the contract provisions of the law and the frauds upon immigrants resulted in strenuous efforts to amend the Act to Encourage Immigration. Lincoln, himself, in his Annual Message to Congress on December 6, 1864, stated, “The act passed at the last session for the encouragement of immigration has, so far, as was possible, been put in operation. It seems to need Amendment, which will enable the officers of the government to prevent the practice of frauds against the immigrants while on their way and on their arrival in the port, so as to secure them here a free choice of vocations and paces of settlement.”

Lincoln’s law continued to attract attention even after his assassination. In the Senate on January 23, 1865, a bill to amend the Act to Encourage Immigration and to amend the Passenger Act of 1855 was referred to the Committee on Commerce. The Senate bill dealt solely with the fraud and passenger aspects of the act. No action, however, was taken by the Senate in the 38th Congress on any of these acts. In the next session, the first of the 39th Congress, both houses acted. This bill gave the Commissioner of Immigration additional power to strengthen the passenger acts; it provided more rigid penalties for violations of these laws and gave the Commissioner power to sue and collect through the courts all penalties. Additional United States Emigrant offices were to be established, in Boston, New Orleans, Baltimore, San Francisco, and Philadelphia, under the direction of superintendents and having the same powers as the superintendent in New York.

Frustration and political pressure was apparent when the Senate considered the House version of the bill on July 23, 1865. The Senate Committee on Commerce surprised everyone when it reported “That the Act entitled An Act to Encourage Immigration, approved July 4, 1864, be and is hereby, repealed.”

The tabling of this measure marked the death of the movement in Congress to amend the Act of 1864. The criticism of the Act of 1864 in the Senate debate may well have been the starting point for the repeal of the only act the Federal government ever passed to encourage immigration. Lincoln’s plan for the country to welcome and embrace immigrants was finally repealed by a section of the Diplomatic and Consular Bill in 1868. No other action was ever taken by Congress to encourage immigration, although two bills were introduced in 1868 purporting to establish immigrant societies abroad under government direction and several states later petitioned Congress for laws to encourage immigration.

Statue of Liberty under construction in Paris

The repeal of Abraham Lincoln’s Act to Encourage Immigration could not, however, remove the effect it had upon immigration. Its important influence and aid to the states, the circulation of its recruiting materials abroad, the publicizing of the attractiveness of America for the immigrant, and the stimulus it gave to private enterprise foretold the massive flow of immigration to the United States in the later part of the nineteenth century. The secondary effects of the act, such as the popularization abroad of another of Lincoln’s landmark laws, the Homestead Law, encouraged thousands of immigrants to come to the United States and settle as farmers in the Midwest and West.

Although he did not live to see the completion of his dream that America would welcome immigrants to its shores as a natural resource and a very valuable ingredient in the nation’s future success, Lincoln nevertheless deserves the credit for initiating a plan that personified Emma Lazrus’ words long before they were memorialized on the Statue of Liberty. For in so doing, the Great Emancipator was also the Great Egalitarian who believed firmly that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution applied to all, regardless of their ethnicity or country of origin. Lincoln’s America would eventually become what he had envisioned: a kind mosaic of all peoples who sought to find a new life within its bountiful borders.

Jason H. Silverman is the Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History at Winthrop University. He is the author of the recently published Lincoln and the Immigrant. He is also a member of the President Lincoln’s Cottage Scholarly Advisory Group.