By Johnny Di Lascio

A Tour of President Lincoln’s Cottage that Almost Didn’t Happen: President Garfield’s Final Visit to the Soldiers’ Home

A month before his assassination, President Garfield visited the same cottage President Lincoln had lived in for over a year of his own presidency. He almost didn’t make it. That very morning, he unknowingly escaped a would-be assassination attempt by a monomaniac determined to take his life. Like Lincoln before him, security concerns took a backseat to accessibility, and it would ultimately prove fatal.

During his presidency, Abraham Lincoln and his family lived in a Gothic-revival cottage, three miles north of the White House, on the grounds of what was then known as the Soldiers’ Home. Among other reasons the Lincolns made the move was to escape from the crowded and at times overwhelming White House. They also were mourning the loss of their son Willie Lincoln, who died in February 1862. While living there, President Lincoln commuted regularly to the White House, or Executive Mansion as it was then known. Sometimes he did this ride alone. Solitary rides to and from the Soldiers’ Home may have been ideal times for contemplation, but they were also potentially dangerous. Away from the safety and security of the White House, Lincoln’s commute took him through some open and unpatrolled sections of the District where it was rumored kidnappers, spies, and assassins lurked. Security concerns heightened after a mysterious bullet knocked Lincoln’s top hat right off his head as he road home to the Cottage one evening in the summer of 1864. “If you value your life,” wrote one concerned Washingtonian, “discontinue your visits out of the city!”[1] Still, Lincoln continued commuting to and from the Cottage, as it gave him a space to reflect, think, and develop new perspectives on issues of freedom, justice, and equality.

Lincoln was not the only president to use the Soldiers’ Home. James Buchanan, Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester Alan Arthur all stayed on the property, and several other presidents recorded visiting the grounds while living in Washington. One such President was James Abram Garfield. Like Lincoln he visited the Soldiers’ Home with an eye towards using it as a potential summer retreat. Unfortunately, also like Lincoln, an assassin’s bullet ended his promising presidency. In fact, just as Lincoln visited the Soldiers’ Home the day before he was shot, so too was Garfield’s last visit to the Soldiers’ Home enveloped in the shroud of assassination.

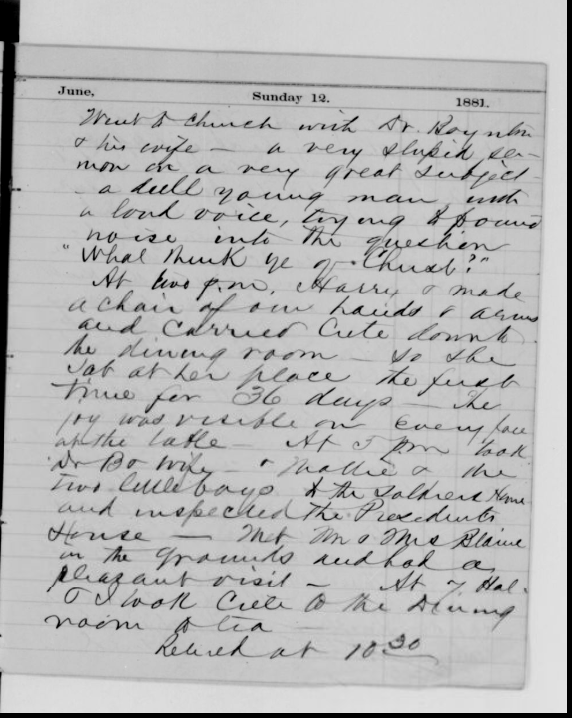

Garfield last visited the Soldiers’ Home on June 12th, 1881 less than a month before his brief presidency was tragically upended. On that particular visit, he was inspecting the Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home to see if the family should stay there. His diary devoted only a single sentence to the trip, but an occurrence noted earlier in the day’s entry makes June 12th notable. While attending a Sunday service that morning, Garfield recalled a strange outburst by a young man during the sermon. Little did he know the young man was Charles Guiteau, his future assassin, who he had planned on shooting Garfield then. Much like Lincoln, who brushed off the possible summer of 1864 attacker as a “foolish gunner with a shot not intended for me,”[2] Garfield also ignored the danger that surrounded him. Three weeks after Guiteau’s outburst in the church Garfield was assassinated.

The lack of security afforded to early presidents is often surprising to our visitors, who are familiar with the high level of security expected for presidents and other elected officials today. Similarly, visitors are often unfamiliar with the incredible access Americans once had to their elected officials, access Lincoln and Garfield both considered essential aspects of a free, democratic government, even if such access caused anxiety and led to security risks.

**

Like Lincoln, Garfield grew up between two visions of America’s future. The free state of Ohio provided opportunities for a person born at the bottom of the ladder to advance, which instilled a strong sense of the transformative power of free labor. At the same time, Ohioans were constantly reminded of the alternative system of slavery, which reigned in the South, by the many fugitives who crossed the state border in search of freedom. Inspired by their stories and repulsed by the wealthy slaveholders who crossed into Ohio in search their escaped property, Garfield cultivated an antislavery belief that informed his entry into politics. Twenty-two years Lincoln’s junior, Garfield consistently identified with a more radical view of abolition, which demanded stronger measures than Lincoln was willing to undertake. Still, if Garfield disagreed with Lincoln’s measured approach to abolition, they shared a belief in the benefit of social mobility, what Lincoln called “the right to rise.” Echoes of Lincoln’s vision, presented in a speech to the 166th Ohio Regiment, of an “open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise, and intelligence that all may have equal privileges in the race of life”[3] can be heard in Garfield’s 1860 oration at a July 4th celebration:

That kind of instability which arises from a free movement and interchange of position among the members of society, which brings one drop up to glisten for a time upon the crest of the highest wave, and then give place to another while it goes down again to mingle with the millions below – such instability is the surest pledge of permanence… the hope of our national perpetuity rests upon that perfect individual freedom which shall forever keep up the circuit of perpetual change. [4]

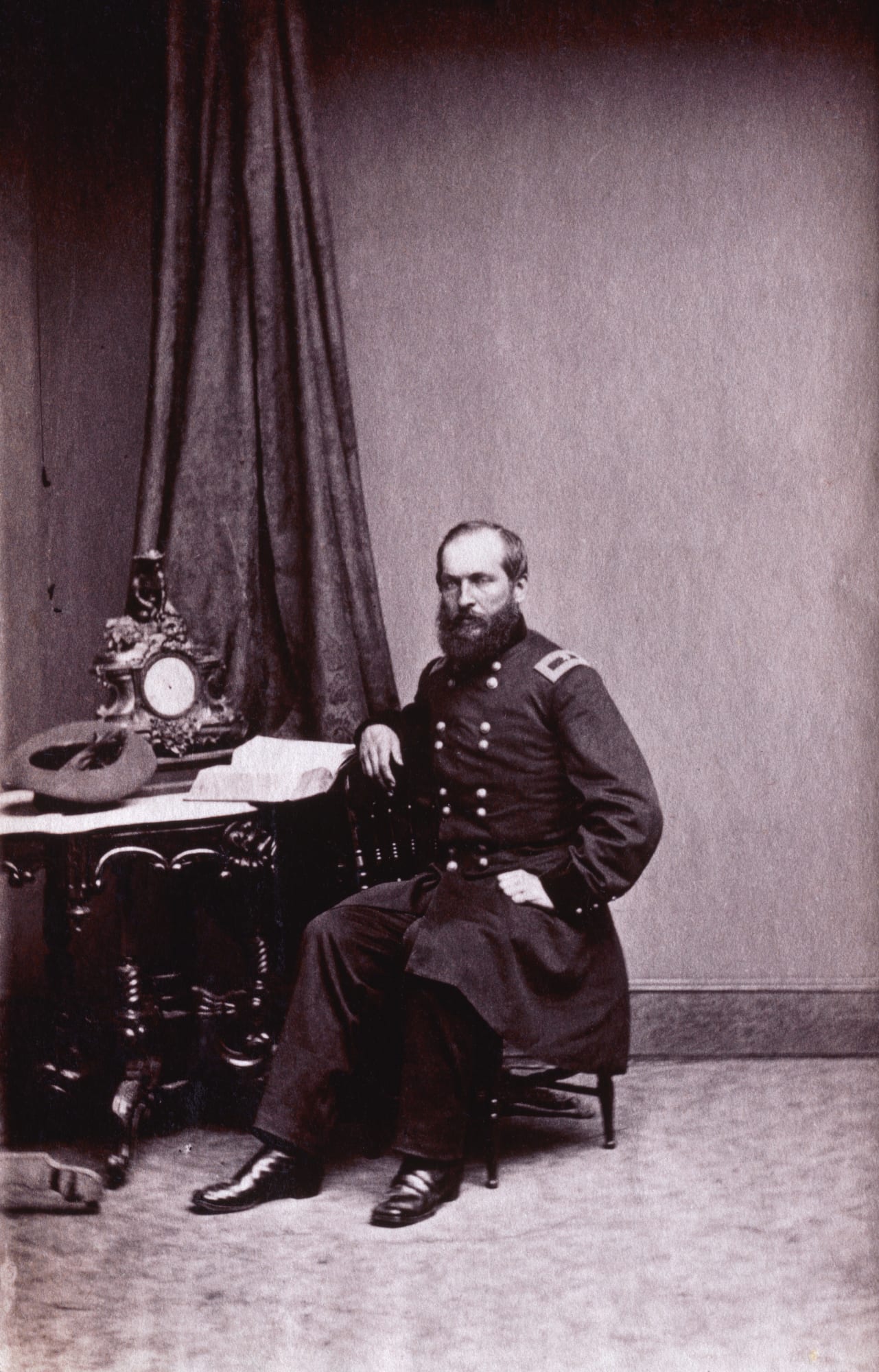

Shortly thereafter, Garfield entered politics. He served in the Ohio Senate from 1859-1861. But the start of the Civil War changed Garfield’s trajectory. Garfield left his seat to join the 42nd Ohio Infantry, and after his impressive performance at the battle at Middle Creek, Kentucky, he rose to the rank of Major General. The victory was a lynch pin in Lincoln’s strategy to keep Kentucky in the Union, a state about which Lincoln once famously quipped “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky!”[5]

Garfield left the battlefield to run for Congress in the 1862 midterms. In many ways, this election served as a referendum on Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which Lincoln had issued while living at the Cottage on September 22, 1862. Though the Democrats made gains in the House that November, Garfield won a seat in Congress and Republicans held both chambers. Arriving in Washington, he soon found allies in the radical abolition wing of the Republican Party, a constant thorn in President Lincoln’s side. Garfield was known to criticize Lincoln’s hesitation to place abolition on the list of Union war aims, as well as Lincoln’s unwillingness to confiscate the farm properties of disloyal southerners. While Northern Democrats often decried Lincoln as a warmonger and dictator, Garfield’s faction thought Lincoln didn’t go far enough. Frustrated with the administration, he joined calls to draft Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase to replace Lincoln for the Republican nomination in 1864. When Chase’s candidacy eventually fizzled, Garfield backed incumbent President Lincoln. Although he’d had a contentious relationship with Lincoln throughout the Civil War, his view shifted in the years after Lincoln died. With hindsight, he called Lincoln, “…one of the few great rulers whose wisdom increased with his power.”[6]

**

After the war, Congressman Garfield poured his efforts into securing the franchise for African Americans, continuing Lincoln’s fight for freedom. He served in Congress for the rest of the 1860s and 1870s, and attended the 1880 Republican National Convention as a delegate. But after a long deadlock between James Blaine, John Sherman, and Ulysses S. Grant – who had come out of retirement to run for an unprecedented third term – Garfield became a dark horse who could bring the fractured convention together. Shouts to draft Garfield soon filled the hall and on the 36th ballot he was duly nominated. Having genuinely not sought his party’s highest honor, the nominee reluctantly accepted. In the extremely tight race that followed, Garfield was narrowly elected the 20th President of the United States over Winfield Scott Hancock.[7]

Cause for celebration quickly turned to frustration as an endless stream of office seekers flooded Garfield’s home in Mentor, Ohio. Things didn’t get much better after he was sworn in, and the new President found himself in a White House perpetually swamped with hopeful job applicants. Garfield had trouble sleeping, in part because of the steady stream of visitors. He believed his day was “frittered away” meeting with the jobseekers “when it ought to be given to the great problem[s] which concern the whole country.” These visitors were like a “Spartan band of disciplined office hunters,” he remarked.[8]

This was not a new practice. Lincoln too had been beseeched by office seekers and other citizens asking favors of the wartime President. His personal secretaries remarked on this constant stream of visitors. “Lincoln seldom if ever declined to receive any man or woman who came to the White House to see him,” John Nicolay noted. John Hay was more caustic about the visitors who had “invaded and overrun” the Executive Mansion, coming “in at daybreak and are still coming in at midnight.”[9]

This easy access to the President increased security concerns especially during the Civil War. Leonard Swett, a lawyer and adviser to Lincoln, urged the President to take his security seriously enough times to make it a sticking point between the two. In response to one such discussion over his safety, Lincoln remarked to Swett “I cannot be shut up in an iron cage and guarded….You may guard me at a single point, but I will necessarily be exposed at others. People come to see me every day and I receive them, and I do not know [if] some of them are secessionists or engaged in plots to kill me.” Separately, Lincoln also remarked that “I cannot discharge my duties if I withdraw myself entirely from the danger of an assault. I see hundreds of strangers every day…To be absolutely safe I should lock myself up in a box.”[10]

For Garfield, security concerns had seemingly evaporated. There was no war, and though he had only won the national popular vote by 1,898 votes, he faced none of the virulent hatred and hostility that plagued Lincoln. However, the very ease of access to the President would once again prove fatal.

**

On April 12, 1881, the Soldiers’ Home Board Meeting notes mention a “unanimous” decision by the “inmates of the home,” to invite President Garfield to spend his summers at the Soldiers’ Home. Garfield hoped to find respite in the cottage and the hundreds of wooded acres of country landscape surrounding it like his presidential predecessors. Sickness in the family affected the new President. Within weeks of moving to Washington, First Lady Lucretia Garfield contracted malaria and lingered on the edge of death. The same unsanitary Washington conditions which plagued the Lincoln family and took the life of their son Willie had not improved much by Garfield’s time. Though Washingtonians had once chided Lincoln for his dangerous rides to the Soldiers’ Home, now they pleaded with the Garfields to head for the breezy hilltop outside the city. An article in the Washington Post the spring after his inauguration urged Garfield to “lose no time in removing his family to the invigorating heights and air of the Soldiers’ Home.”[11]

In advance of his move to the Soldiers’ Home, Garfield made several short visits to the site, including one on the afternoon of June 12. The president briefly mentioned it in his diary entry for the day:

At 5 pm took Dr. Bo wife, Mollie, and the two little boys to the Soldiers’ Home and inspected the President’s House.[12]

It is easy to imagine the visit as carefree family time in the quiet pastoral setting of the Soldiers’ Home hilltop, but this idyllic scene was in stark contrast to the perilous trial Garfield had unknowingly passed through that morning.

June 12, 1881 was a Sunday, and Garfield spent the morning at the Vermont Avenue Church. He was a devout Christian, but it was the first Sunday in many months the overwhelmed president finally had time to attend a service. As Garfield listened to what he would later describe in his diary as a “very stupid sermon,” a man sat in the back row, eyes fixed on him. Unlike Garfield, this man was not in church to listen to a sermon, but to change history.

For the last month, Charles Guiteau, an emotionally unstable outcast suffering delusions of grandeur, had been stalking President Garfield with the intent to kill him. Guiteau believed he deserved to be appointed ambassador to France or Austria for his efforts to elect Garfield, though his effect on the 1880 election had only amounted to writing and publishing a mediocre speech advocating for Garfield. He even briefly met the President the week after his inauguration, on March 8, 1881, providing a copy of the speech he believed warranted a consulship. He continued to press his case, visiting the White House often, pestering Cabinet Members and other political figures in person, and writing dozens of letters on stationery from fancy hotels and boardinghouses to look impressive. Eventually, he was banned from the White House waiting room on May 13, and the next day the Secretary of State James Blaine told him “Never speak to me again of the Paris consulship as long as you live.”[13]

Guiteau saw no malice in the act he aimed to commit; he liked and admired President Garfield. This was strictly business: Guiteau wanted a job in the Garfield administration and the President refused. Removing Garfield would put Chester Alan Arthur in the White House, and Guiteau, the hero, believed he would be rewarded with a coveted position. Though the idea that someone would get a job in a presidential administration after assassinating the prior president is quite ludicrous, Guiteau’s mind had long led him down erratic and dangerous paths. By the spring of 1881, Guiteau was fully engaged in the effort to carry out his bizarre plan to advance his career.

On June 12, Guiteau sat in the back pew of the Vermont Avenue Church trying to find the perfect angle to fire a single shot into the back of Garfield’s head without injuring any other congregants. He reasoned, with Hamlet-like logic, that killing Garfield in a church would ensure the martyred president’s immediate passage into heaven. Since he liked his target, this was a desired outcome. Little by little, his attention drifted toward the words coming from the pulpit. Losing himself in the pastor’s sermon, Guiteau, himself a revivalist preacher, became increasingly agitated until he abruptly shouted “What think ye of Christ!” An awkward silence hushed across in the congregation. The would-be assassin left and returned to his room at the Riggs Boarding House at 15th and G.[14] President Garfield logged the young man’s outburst later that evening in his diary:

Went to church with Dr. Boynton and his wife – a very stupid sermon on a very great subject a dull young man with a loud voice, trying to pound noise into the question [shouted] “What think ye of Christ?[15]

Unaware of the danger posed by that “dull young man,” Garfield moved on with his day, eventually heading to the Soldiers’ Home at 5pm. For the rest of June, Guiteau continued to stalk Garfield.

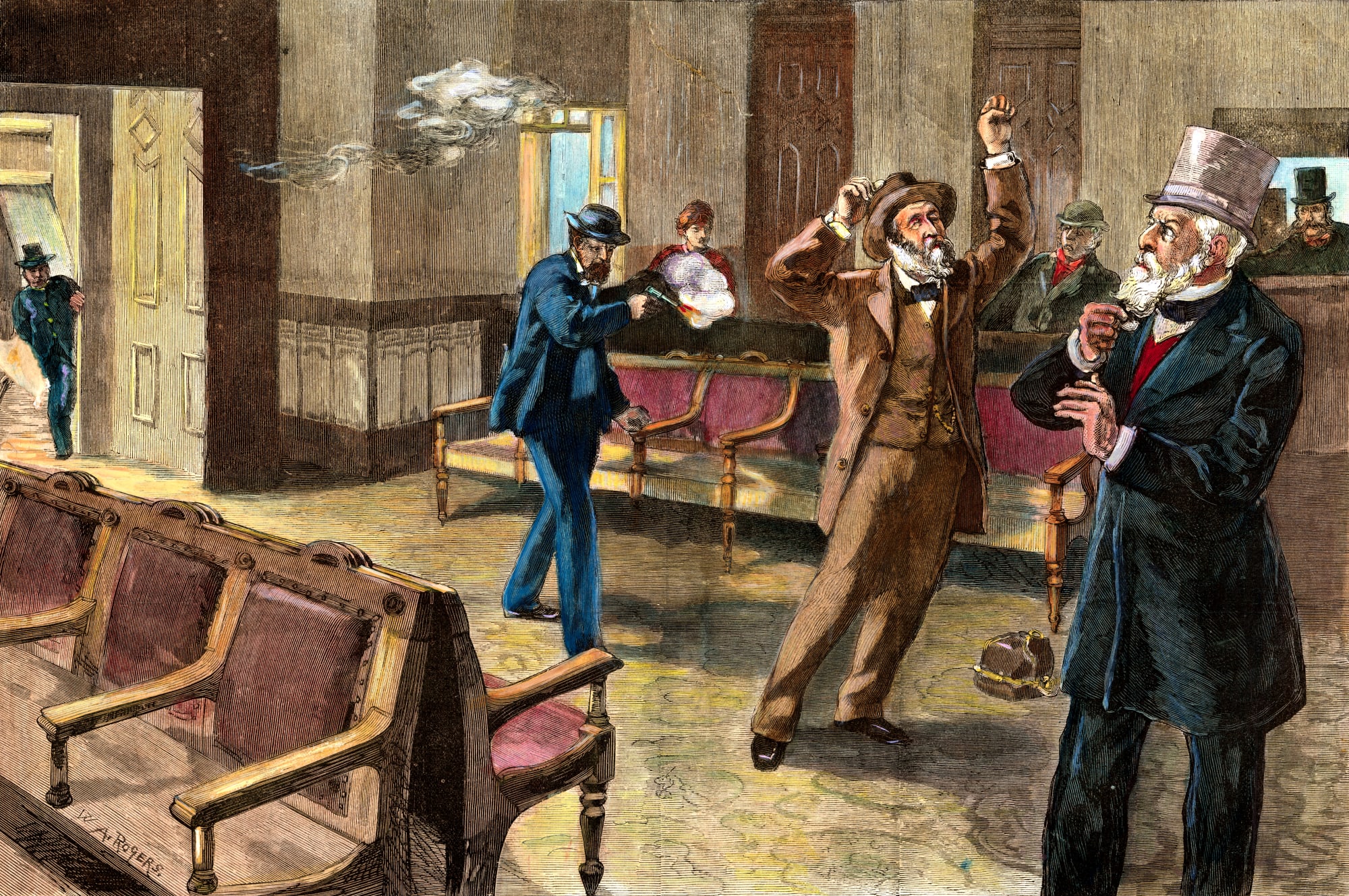

On July 2nd, as the President prepared to leave Washington for a summer vacation, Guiteau was waiting for him at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station (located where the National Gallery of Art is today). The newspapers had reported that Garfield would be leaving for his vacation from the train station, providing a potential opportunity for the assassin to strike given the easy access to the President. When Garfield entered the lobby, Guiteau raised his arm and fired two shots: one grazed the president’s arm, the other struck him soundly in the back, knocking him to the ground. (Ironically, one person meeting Garfield at the train station that day was his Secretary of War: Robert Lincoln. Present at his own father’s deathbed, and nearby when Garfield was shot, Robert also was nearby when an assassin’s bullet took down President William McKinley in 1901.) Garfield initially survived, but the long and brutal struggle against death was only beginning.

Garfield’s chances of survival were diminished when a prima donna doctor named Willard Bliss was appointed to oversee the president’s recovery. Dr. Bliss did not subscribe to the new theory that germs spread disease; his endless unsanitary probes contaminated the president’s wound. Garfield quickly developed gangrene and sepsis. Over the next three months while the president lay dying, the nation was wrapped in the drama unfolding in Washington. Although a great tragedy was underway, some proposed innovative solutions that led to later inventions. First Lady Lucretia Garfield believed using large amounts of ice could cool her husband’s sick room. Working with the U.S. Army Engineers and White House staff, Lucretia’s idea led to a sort of primitive air conditioning. “It is now possible to place the temperature and humidity of definite quantities of air at any point that may be desired” read one report on the new invention.[16]

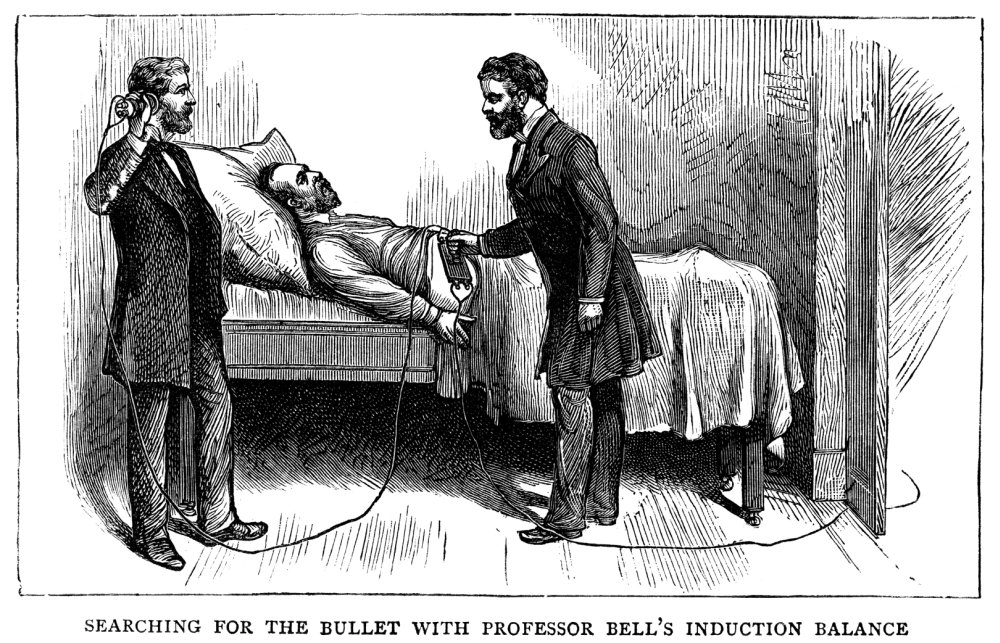

The air conditioner wasn’t the only invention sparked by Garfield’s condition. Scottish inventor Alexander Graham Bell worked on another new technology to attempt to locate and remove the bullet which was lodged somewhere inside the President’s abdomen. Bell had recently been excited by a newly invented device called an induction balance which could generate an electric current by passing charged coils over a mass, such as a human body. Any metal which might be inside that body would noticeably interrupt the current. Applying his telephone technology which allowed him to use electric currents to amplify a human voice, Bell’s metal detector amplified the sound of the electric current interrupted by the presence of metal. Thus if it ran the coils over Garfield’s body, doctors could find the bullet.

From his Volta Lab on Connecticut Avenue in Washington, Bell worked tirelessly on his bullet finding machine. Assembling an early prototype, Bell looked for guinea pigs to test it on first. Since the Civil War, countless veterans lived with the bullets still lodged in their bodies. Often, this factor contributed to their deteriorated health and shortened life spans. It also made them perfect subjects for the trials of Bell’s invention.

On July 31, he ventured to a site where he was certain to encounter war veterans: The Soldiers’ Home. There he met with resident Private James McGill, who was wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill and for twenty years carried the bullet inside him. Bell ran his coils over Private McGill and easily found the bullet. McGill would be the first of many soldiers to benefit from Bell’s hastily constructed metal detector. Though the invention of the x-ray fifteen years later would revolutionize veteran healthcare, Bell’s metal detector contributed to the locating and removal of bullets inside many Civil War heroes. Sadly, the man Bell had in mind when he built it, would not be saved by it.

When Bell came to the White House to try the metal detector on President Garfield, Dr. Bliss gave very specific instructions on where Bell could search for the bullet. Bliss was sure he already knew the location of the bullet and only allowed Bell to point the detector at the spot he mistakenly believed harbored it. As Bell ran the coils over the wrong spot, Lucretia listened into an earpiece in another room. The First Lady regretfully reported no sound. Metal coils in the bed also possibly interfered with Bell’s machine. Whatever the case, his device appeared to have failed. A devastated Bell was ushered out of the room and with him the president’s last hope of survival.

As the tragedy was unfolding, Garfield’s children took another trip to the Soldiers’ Home on July 30, the day before Bell’s visit. As it had for the Lincolns following the death of Willie, the peaceful site gave refuge in times of sadness and uncertainty. The President’s eldest daughter Mollie recounted,

When we got to W. [Washington] we all rode out to the Soldiers’ Home & spent a delightful evening, reaching home about 9 P.M. Oh, I have had just what I call a jolly good time. But I fear I won’t get to sleep because I drank coffee.[17]

By September, Garfield had reached the point of no return. The President insisted he be taken out of the swampy U.S. capital and allowed to die in the serene ocean climate of Elberon, New Jersey. A special train was designated for the President and several miles of extra track were hastily laid down to carry him directly to his doorstep. Garfield spent his final days caressed by an ocean breeze as he gazed across the waves toward the horizon.

The senseless death of the President devastated the nation, especially just 16 years after Lincoln’s death. Soon a drama of a whole different sort emerged. Guiteau’s trial proved to be national spectacle, with constant coverage of his outrageous behavior. The assassin’s brother-in-law initially served as his lawyer, but Guiteau often stepped out to question witnesses himself. He would go on long rants to the jury, even sometimes breaking into song. Guiteau may have been angling for a not guilty by reason of insanity verdict, but the jury wasn’t playing along. Guiteau was found guilty and sentenced to death. Within a year of shooting President Garfield, Guiteau was hanged. His flowing confessions have left historians with ample material to piece together his entire timeline during the months leading up to the crime, including his many attempts to meet with the President and other politicians, as well as his visit to the Vermont Avenue Church on June 12.

For Garfield, June 12 was a day of contrasts. In the morning, he sat in the cross-hairs of a determined assassin. By late afternoon, he was enjoying the soft breeze overlooking a broad vista of Washington City. Garfield did not write much about his visit to the Soldiers’ Home — just like Lincoln did not write often about the site — but the remembrance of one reporter who was close to the President offer clues as to what he was like in his leisure time:

Here was a man who loved to play croquet and romp with his boys upon his lawn…who read Tennyson and Longfellow at fifty with as much enthusiastic pleasure at twenty, who walked at evening with his arm around the neck of a friend in affectionate conversation, and whose sweet, sunny, loving nature not even twenty years of political strife could warp.[18]

It is easy to imagine such scenes taking place at the Cottage and the surrounding grounds. But that was not to be, thanks to the easy access that Americans, all Americans — the humble, the ambitious, the valiant, and the sinister — had to the president in the 19th century.

Johnny Di Lascio is a Museum Program Associate at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Quote in Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home (Oxford University Press: New York, 2003), 145.

[2] The Public Service Review, Volume 1 Public Service Publishing Company, 1887. https://books.google.com/books?id=XzZNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA158&dq=a+foolish+gunner+with+a+shot+not+intended+for+me+Lincoln&

[3] Roy P. Basler, ed. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7:512.

[4] Quoted in Adam Goodheart, 1861: The Civil War Awakening (New York: Albert A. Knopf, 2011), 94

4 https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0013.104/–abraham-lincoln-and-the-border-states?rgn=main;view=fulltext

[6] Robert Granville Caldwell, James A. Garfield: Party Chieftain. New York, New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. (1965) [1931].

[7] Not to be confused with Soldiers’ Home founder Winfield Scott, after whom Hancock was named.

[8] James C. Clark, The Murder of James Garfield, Prologue, 1992 Summer, page 129. https://www.archives.gov/files/publications/prologue/1992/summer/garfield.pdf

[9] Quotes from Ron J. Keller, “Lincoln in His Shop” https://www.whitehousehistory.org/lincoln-in-his-shop.

[10] Both quotes can be found in: Brendan H. Egan, Jr., Murder at Ford’s Theatre: A Chronicle of an Assassination (Xlibris US, 2008), 19.

[11] Washington Post May 12, 1881, cited in Erin Carlson Mast, Garfield Enjoyed Soldiers’ Home Grounds, https://www.lincolncottage.org/garfield-enjoyed-soldiers-home-grounds/

[12] James A. Garfield Papers: Series 1, Diaries, 1848-1881; Vols. 19-21, 1879, Oct.-1881, July. 605.

[13] Candace Millard, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of the President (New York: Random House, 20110, 107-108.

[14] The Riggs House was built by Banker George Washington Riggs, the original owner of the Cottage, between 1859-1860. http://www.streetsofwashington.com/2009/11/and-one-block-north.html

[15] James A. Garfield Papers: Series 1, Diaries, 1848-1881; Vols. 19-21, 1879, Oct.-1881, July 605.

[16] Army and Navy journal November 12, 1881 https://books.google.com/books?id=Xvg-AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA322&dq=it+is+now+possible+to+place+the+temperature+and+humidity++of+definite+quantities+of+air+at+any+1881

[17] The Diary of Mollie Garfield, excerpted in Mollie Garfield in the White House by Ruth

Stanley-Brown Feis, Rand McNally & Co., 1963, cited in Mast Garfield Enjoyed Soldier’s Home.

[18] Quoted in Millard, Destiny of the Republic, 248.