by Curtis Harris

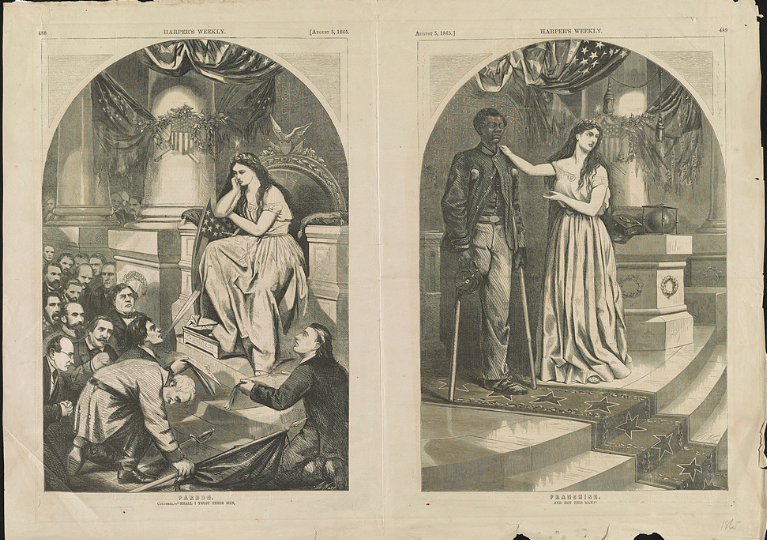

Although the Civil War concluded over 150 years ago, Americans still struggle to comprehend and understand the full weight of the war’s impact. If we today struggle with that weight, it’s understandable that Americans in 1866 were even more flummoxed. Yes, slavery had been the source and cause of the war, but what would be the lasting result of the terrible civil conflict that had just ended?

At the forefront of the debate was the status of African Americans, both emancipated and those born free. Would black Americans continue to have “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” as envisioned by the late Justice Roger Taney in the Dred Scott Decision of 1857? Or would they have new rights to enjoy beyond freedom from slavery?

By offering his own interpretation during his last public speech on April 11, 1865, Lincoln became the first president to advocate for any measure of black voting rights. This first public expression of his views came after he privately pressed for this measure to Louisiana’s then-governor Michael Hahn in the preceding year. Although his proposal for black suffrage was limited to males who had fought in the U.S. military or were deemed “intelligent,” this was a watershed moment in American politics. The significance of the moment was not lost on Lincoln’s audience. Days later, John Wilkes Booth, an unhappy attendee at the speech where Lincoln advocated black suffrage, showed the sharp and bloody trials awaiting the nation during Reconstruction.

During this moment of uncertainty where the Civil War had ended militarily, the heated ideological conflict persisted. Southern state governments quickly came under the control of ex-Confederates, buoyed by lenient clemency from President Andrew Johnson, and instituted Black Codes restricting the freed people’s rights. Opposing these actions was an increasingly exasperated Republican Congress that came to view these laws and wanton violence as affronts to not only the freed people themselves, but also to the sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of people who had lost their lives restoring the Union and destroying slavery.

On April 9, 1866, just a year after Lincoln’s final speech and death, the United States Congress, over the veto of a belligerent President Johnson, passed the very first Civil Rights Act (CRA) in American history. Soon after the 14th Amendment followed enshrining that law’s precepts permanently in the Constitution. The CRA of 1866 and the 14th Amendment, however, did not resolve the question of the Civil War’s final meaning for that generation or the ones that followed.

Emancipation and Black Codes

Nearly eight months after Lincoln’s murder, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865. This measure at last declared that “slavery and involuntary servitude” would no longer exist, except as punishment for crimes. In the immediate aftermath of emancipation, however, the Southern state governments set about passing Black Codes, which denied any semblance of civil, political, racial, or social equality between the formerly enslaved and their erstwhile masters.

Indeed, these laws in many ways mocked the idea of emancipation and freedom of movement. Although the particulars varied by state, a common theme was requiring black people receive the permission of their current employer before seeking new employment elsewhere. And any white businessman caught enticing the worker of another would face punishment as well. Mississippi’s Black Codes imposed a tax on all black people ages 18-60. Failure to pay the tax gave the state the power to “hire out” the black person to anyone who would pay the tax on their behalf. A similar system arose for black people convicted of vagrancy, which evolved into a massive system of convict labor by 1900 that has been described as “slavery by another name.”

Despite the chaffing and oppressive laws, President Johnson’s plan of Reconstruction (Presidential Reconstruction) rapidly readmitted Southern states and allowed many former Confederate officials back into positions of power within the United States less than a year after military hostilities had ceased. This perceived affront, coupled with the Black Codes that severely restricted the rights of African Americans, made many Northerners wonder who had actually won the Civil War.

Concrete and odious evidence of abuses, as reported by the Freedmen’s Bureau, began pouring in to Congress whose Republican members grew more hostile by the moment toward Presidential Reconstruction. A report submitted in March 1867 chronicled abuses that had occurred in Louisiana since the summer of 1865. Below are just two examples of dozens of outrages included in the dossier.

[teaser]Report from St. Tamany Parish, July 9th, 1865[/teaser]

“About 5 o’clock p.m. Hardy, a freedman, was going home from church when Lovitt, Marshal of Amite City asked the freedman for his pass, who replied ‘he had none nor did he consider it necessary now.’ Lovitt then struck him over the head with his pistol, and on his running off fired at him twice, wounding a white man who was standing near. When the freedman reached the main street a man in a coffee house emptied his revolver at him, two balls taking effect in his body. The freedman was very dangerously wounded. Military authorities tried to arrest parties but failed. Civil Authorities did nothing.”

[teaser]Report from Bossier Parish, December 24th, 1865[/teaser]

“Nelson Logan, freedman, complains that a party of about 30 of the Bossier Parish Militia commanded by N. Taylor, came to plantation of John Adams in Bossier Parish in search of arms, took Logan to the woods and hung him by the neck till he was senseless. Only remembered four of the gang (viz., N. Taylor, R. Matthews, G. McAlley & James Carter – all returned Confederate soldiers).”

The Civil Rights Act of 1866

The reports from the Freedmen’s Bureau spurred Republicans to organize a federal bill to protect the rights of the freed people. Proposed and authored by Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 became the first civil rights bill in American history. Unimpressed by the measure, President Johnson promptly issued a veto.

Claiming that it discriminated against white Americans, Johnson’s veto message on March 27, 1866, chided Congress for “establish[ing] for the security of the colored race safeguards which go infinitely beyond any that the General Government has ever provided for the white race. In fact, the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race.”

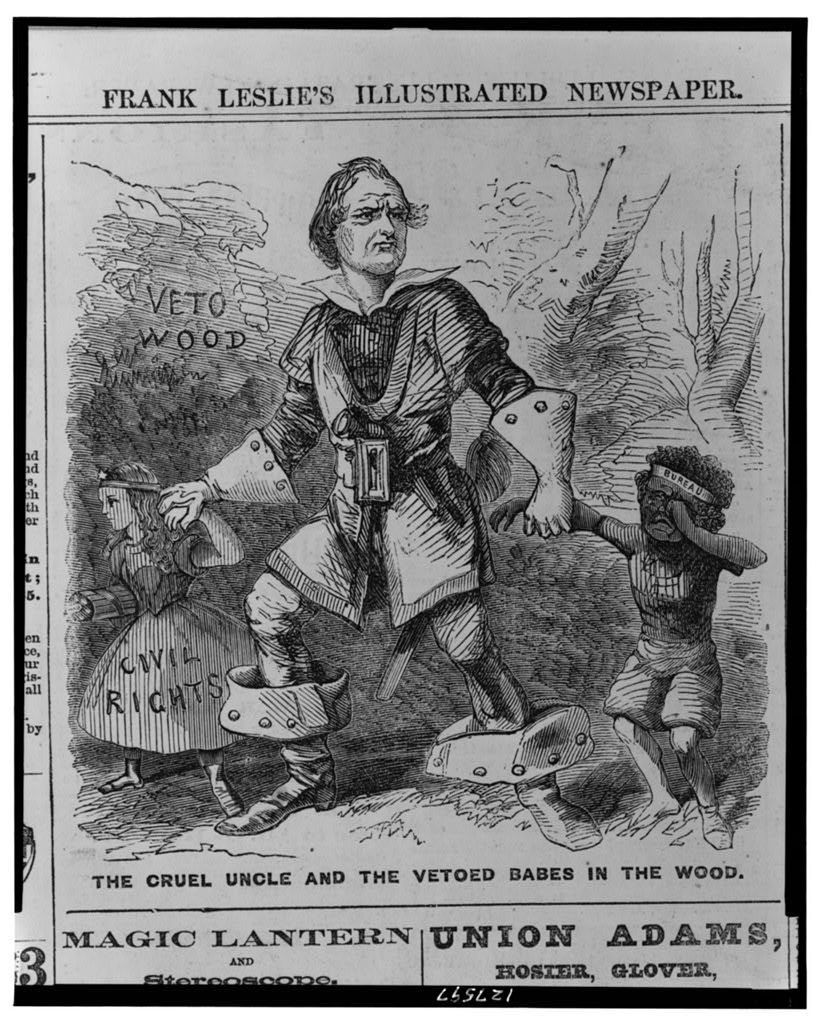

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Paper sarcastically portrayed President Johnson’s dismissal of the CRA and also his antipathy for the Freedmen’s Bureau with a cartoon entitled “The Cruel Uncle and the Vetoed Babes in the Wood.”

Cruel Uncle Andrew’s veto was promptly overridden by the Congress and the bill became law on April 9, 1866.

Section 1 of the CRA began with this sweeping repudiation of the Dred Scott Decision, which had been delivered just nine years earlier :

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States…”

The CRA then specified that “such citizens, of every race and color” would have:

“the same right, in every State and Territory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties…”

Sections 2 through 10 of the CRA then outlined enforcement mechanisms and punishment for those who would violate the civil rights of other Americans. The power of the CRA was quickly tested, however, as events in Memphis and New Orleans soon cast doubt on whether civil rights could be fully protected by a mere act of Congress, especially with a President in office who had vetoed the notion of black civil rights. Indeed the scale of the violence that enveloped the two cities called into question whether violent civil conflict had ended with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox a year before.

[teaser]It was no riot; it was an absolute massacre.[/teaser]

Standing on the banks of the Mississippi River, Memphis and New Orleans had fallen to the United States Army in early 1862. Therefore by 1866, both cities had been under “reconstruction” for quite some time and had seen their populations of freed people grow considerably well before the 13th Amendment and even the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. Nonetheless, both cities experienced incredible waves of racial violence meant to halt the advance of black civil rights and maintain white supremacy.

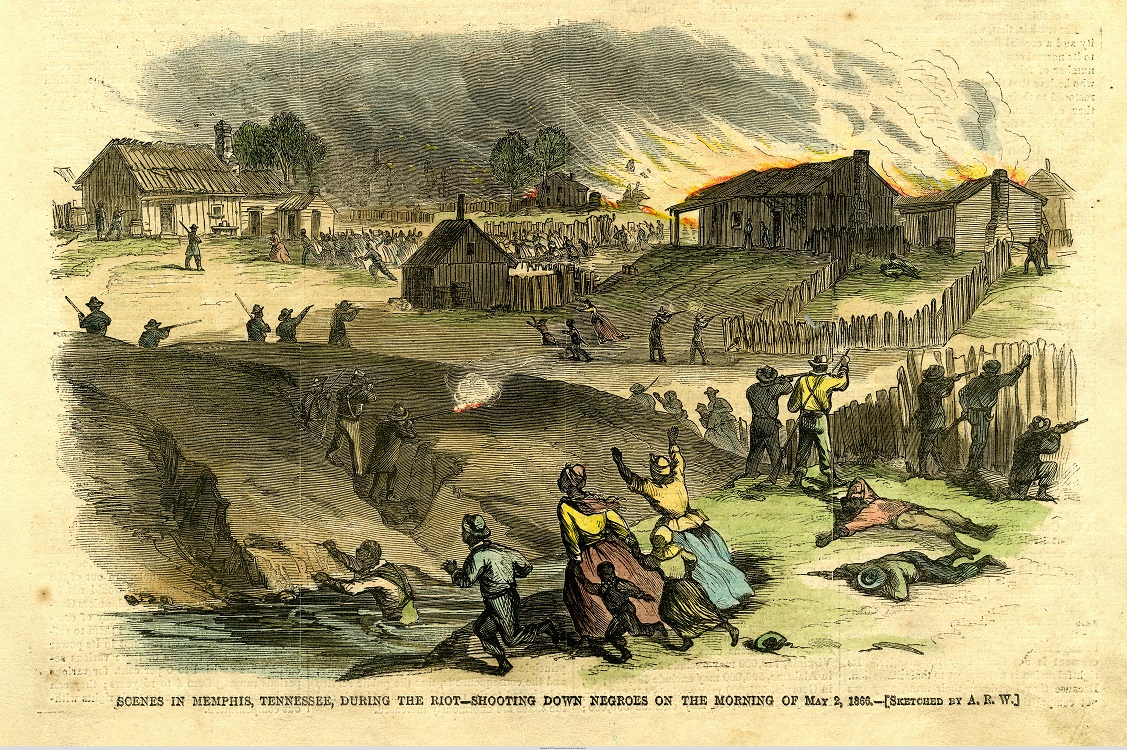

The Memphis Massacre occurred May 1-3 in 1866, less than a month after the CRA’s passage. It started out as a turf skirmish between the white police force of Memphis and a group of black Army soldiers. The minor skirmish quickly escalated into a full-on massacre as the white police force overran the soldiers and, when joined by white civilians, descended upon black neighborhoods of the city killing and raping their residents.

In the end over 40 black Memphians were dead. In comparison just three whites died in the violence and all killed by other whites: a policeman, who accidentally shot himself; a fireman, shot after being mistaken for a black man; and a saloon patron shot for conversing with a black acquaintance during the riot. In addition dozens of homes as well as churches and schools of African Americans were torched during the violence.

Northern opinion immediately denounced the massacre. The Chicago Tribune caustically noted “the Memphis riots exhibit to the gaze of Congress and the country, the marvellous progress the Johnson policy of reconstruction has made in West Tennessee.” African Americans in Memphis, according to Benjamin Runkle, were deflated that the promise of the recently passed Civil Rights Act could be followed so swiftly by wanton violence. Perhaps more painful for the victims was that, ultimately, no government prosecution of the perpetrators followed as local authorities refused to act and the Attorney General, James Speed, believed the federal government had no jurisdiction in the matter.

Runkle, an Army veteran and official in the Freedmen’s Bureau, testified to Congress on June 5, 1866 about black sentiment after the massacre. Runkle noted that “when they come to me [now] they say, ‘You are the man we expected to protect us’;… they have had very little confidence in me or in the government since [the riot].” Shocking as Memphis was, Philip Dray notes in Capitol Men, “Even more potent in its effect on Northern opinion was another ‘riot’ in New Orleans, which occurred at the end of July.”

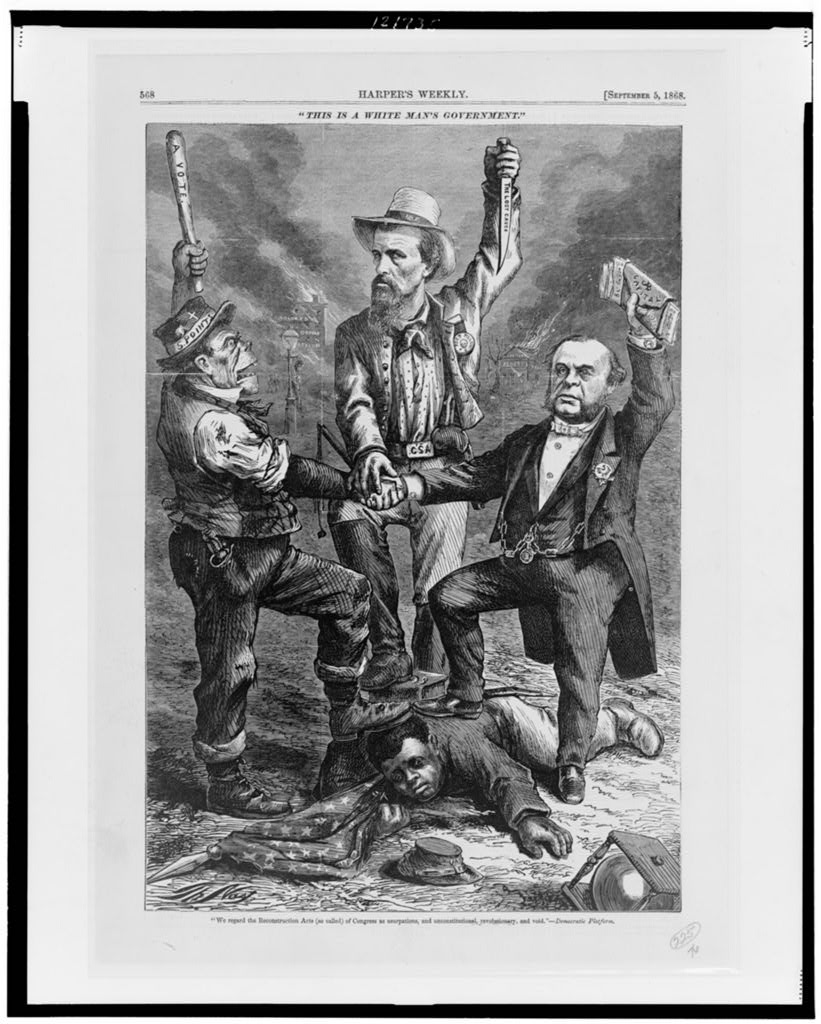

“This is a White Man’s Government” by the satirical Thomas Nast in 1868

The July 30, 1866, massacre in New Orleans began when black and white Louisianians gathered in the city to agitate for a new state constitution that would remove racial discrimination in voting. Their demand echoed the sentiment expressed by Lincoln in his last speech in April 1865. Alarmingly, like Lincoln, their views were met with murderous violence. The meeting was attacked by the local police force and Confederate Army veterans. The New Orleans Daily Picayune quoted one Confederate veteran as saying, “We have fought four years these god-damned Yankees and sons of bitches in the field, and now we will fight them in the city.”

General Philip Sheridan wrote to Ulysses Grant after the incident, “The more information I obtain of the affair the more revolting it becomes.” Sheridan concluded that “It was no riot; it was an absolute massacre.” General Sheridan also offered words of advice to President Johnson warning that “if this matter is permitted to pass over without thorough and determined prosecution of those engaged in it, we may look out for frequent scenes of the same kind, not only here but in other places.”

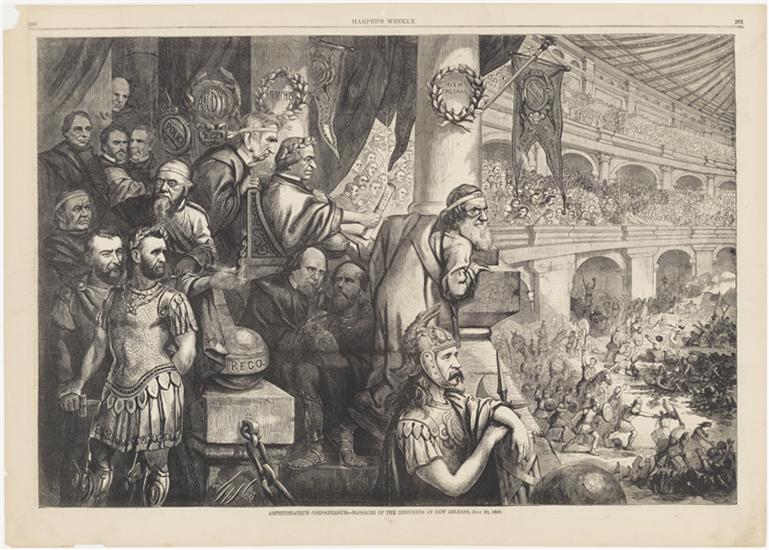

Harper’s Weekly reported on Congress’s investigation into the massacre, which concluded in March 1867. The report confirmed 38 deaths of “loyal men” (34 black and 4 white) and one death of a white police officer from sunstroke. Another 136 loyal men were wounded (119 black and 17 white) including Michael Hahn. The former governor, whom Lincoln had corresponded with on black voting rights, was shot in the back of the head during the violence. Meanwhile only 10 of the assailants were slightly wounded. Despite the evidence amassed, a local grand jury refused to indict anyone for the deaths. The grand jury instead blamed “political tricksters” who organized the political meeting for inciting the incident.

Channeling Northern indignation with President Johnson’s refusal to enforce the Civil Rights Act and inability to restore any semblance of fair order in the South, cartoonist Thomas Nast created a scathing illustration for Harper’s Weekly. The cartoon portrayed Johnson’s indifference at the violence in New Orleans and Memphis as that of a Roman emperor overseeing a gladiatorial spectacle.

That fall, Northern voters returned a stunning Republican majority to Congress. Republicans controlled 175 of the 224 seats in the House, a whopping 78{ec117f0059f8cde3a5e4f5b3c1b486659702d407977a37ffc575d2c0a9b4a69f}. In the Senate, the Republican Party assumed 57 of the 66 seats, a stunning 86{ec117f0059f8cde3a5e4f5b3c1b486659702d407977a37ffc575d2c0a9b4a69f}. These massive majorities created a veto-proof power that would take the reins of Reconstruction completely from the hands of the president.

The Constant Reconstruction

Prior to the violence of New Orleans and Memphis, congressional Republicans were already devising an amendment to the Constitution to permanently protect the civil rights of Americans. The intransigence of President Johnson made it obvious that these civil rights, if protected only by a law, could be upended by future presidents who weakly enforced it or congressmen who could repeal the act. Many moderate Republicans, such as John Bingham of Ohio, although favorable to the CRA, also expressed concern that Congress didn’t have the constitutional authority to protect the rights expressed in the Act. Indeed, Bingham would author the 14th Amendment and begin its path toward ratification, which would assuage the qualms mentioned above.

The violence in the South merely added another layer of urgency to the matter and sensitized many Northern whites to the necessity of the Amendment, hence the overwhelming majority Republicans received in the fall of 1866.

Just a week after the violence in Memphis, Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens cited the massacre as further reason to move full speed ahead with the 14th Amendment as the next measure to ideologically conclude the Civil War: “Let not these friends of secession sing to me their siren song of peace and good will until they can stop my ears to the screams and groans of the dying victims at Memphis.” The 14th Amendment passed both houses of Congress a month after the Memphis Massacre in early June 1866. By the end of the month, Connecticut became the first state to ratify the Amendment.

No longer fearing Johnson’s veto power, the new Congress that assembled after the elections passed their first of four Reconstruction Acts (over Johnson’s veto, of course) in March 1867 ushering what is known as Radical Reconstruction. The First Reconstruction Act placed all of the former Confederate states into military districts unless they ratified the 14th Amendment. Tennessee was the only former Confederate state to ratify the Amendment by that point, therefore the other 10 Southern states were placed under direct federal military oversight. These states slowly regained representation in Congress – often with black congressmen – after passing the 14th Amendment.

The ultimate ratification of the 14th Amendment by July 1868 revealed a new wrinkle to the evolving debate on the meaning and purpose of the Civil War. The Amendment not only solidified the CRA of 1866 and its birthright citizenship provision, it also placed the federal government into the business of individual voting rights. Section 2 of the Amendment provided a mechanism for Congress to reduce a state’s representation in the House of Representatives if that state denied the right to vote to men over the age of 21.

This tentative measure was unflattering to some like Stevens and Frederick Douglass who would have preferred a more rigorous defense of voting rights. In November 1867, Douglass thundered, “Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex.” Women’s suffrage would have to wait five decades, but voting rights for black men were protected by the 15th Amendment in 1870 that outright forbade disfranchisement due to “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Poster celebrating passage of the 15th Amendment and civil rights advocates

Radical Reconstruction continued pushing for civil rights and an end to violence via three Force Acts passed in 1870 and 1871, which enforced the 15th Amendment’s voting rights protections as well as targeting vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Meanwhile, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 banned racial discrimination in public accommodations.

Despite these Acts, the violence continued as did creative avoidance of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendment’s civil and political protections.

These laws and amendments also met the rocky shoals of judicial interpretation, which began to sanction a new reconstruction of the country’s meaning away from the Radical Reconstruction vision. In a series of suits deemed the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, the Supreme Court declared the CRA of 1875 unconstitutional. Only Justice John Harlan dissented. Remaining protections for civil rights were further gutted when “separate but equal” became acceptable in the 1896 Plessy v. Fergusson case. Justice Harlan’s impassioned, solitary dissent in Plessy argued that “The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved…”

After decades of protest, lawsuit, and introspection, a majority of Americans again reconstructed the meaning of their country and came to view Harlan’s logic as the proper affirmation of the nation. In that spirit, the Supreme Court reversed itself declaring segregation unconstitutional and Congress passed the first CRA since 1875 when the Civil Rights Act of 1957 became law. The 1964 CRA followed as did a Voting Rights Act in 1965, both measures that hearkened back to the Radical Reconstruction legislation of a century before.

In recent years, it seems not a single Supreme Court or legislative session goes by without a new lawsuit or act designed to once again reconstruct or reinterpret what civil and political rights mean for Americans. As we gather in 2016 and beyond to consider Lincoln’s legacy it’s clear that we still search for answers to the ultimate meaning of the Civil War and of civil rights for the United States.

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

A Massacre in Memphis by Stephen Ash

Lincoln’s Last Speech by Louis Masur

Capitol Men by Philip Dray

Democracy Reborn by Garrett Epps

All images courtesy of the Library of Congress

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Curtis Harris is a doctoral history student at American University. He has worked at President Lincoln’s Cottage for over five years, currently as a Museum Program Associate and formerly as Marketing & Membership Coordinator.